In school districts nationwide, certain groups of students—including Black youth, Latino youth, LGBTQ youth, gender non-conforming youth, and youth with special education needs—are punished at higher rates than their peers. Research shows that these students are punished more frequently and more harshly than their peers, even though they are not more likely to misbehave.

Studies have shown that these unfair rates of punishment can often be attributed to the unconscious, or implicit, biases of educators. Implicit biases are the judgments and beliefs that everyone carries that are unintentional and automatic. These judgments and beliefs may actually be different than those that we explicitly express. Implicit biases are developed from the messages we have picked up from many sources over the course of our lives, and allow our brains to quickly sort objects, beliefs, and even people, into categories. While this quick sorting can be helpful in some situations, it is extremely harmful when we make unconscious assumptions about people based on their race, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or other personal characteristics.

Studies have shown that these unfair rates of punishment can often be attributed to the unconscious, or implicit, biases of educators. Implicit biases are the judgments and beliefs that everyone carries that are unintentional and automatic. These judgments and beliefs may actually be different than those that we explicitly express. Implicit biases are developed from the messages we have picked up from many sources over the course of our lives, and allow our brains to quickly sort objects, beliefs, and even people, into categories. While this quick sorting can be helpful in some situations, it is extremely harmful when we make unconscious assumptions about people based on their race, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or other personal characteristics.

For example, if someone has only been exposed to white male doctors for their entire life and has only seen images on television and in movies of white male doctors, they might, unconsciously, be less likely to trust the abilities of a Black woman doctor because she does not fit the image they have in their heads of what a doctor should look like. This can happen even if the person can outwardly acknowledge that such an assumption is wrong.

These biases are especially harmful because they influence our behaviors even if we do not consciously endorse the stereotypes fueling them. Like many other people, educators and school police officers make unconscious judgments about students based on stereotypes. Reliance on biases increases in high pressure situations or when there are time constraints—exactly the conditions that teachers and officers may experience in schools. These judgments can lead educators and school police officers to punish some students more frequently and more harshly than other students for the same behaviors.

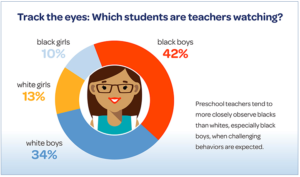

A 2016 study that tracked the eye movements of preschool teachers showed that they were more likely to look for, and identify, “misbehavior” among Black boys, even though none of the children they were observing were behaving in a way that warranted punishment. Most of those teachers likely did not want to target Black children for punishment, yet their implicit biases lead them to unfairly identify those particular students as being in need of punitive discipline.

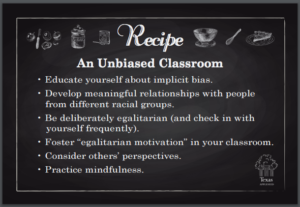

Acknowledging implicit bias does not, by itself, solve the discriminatory outcomes inherent in the use of punitive school discipline. Even using debiasing techniques, like those on the card below, does not guarantee a totally bias-free education system. We must also use implicit bias as a vehicle to have important conversations about race, gender, sexual orientation, disabilities and overall school climate and equity. Understanding bias and having difficult conversations about systemic inequities can also help to identify opportunities for structural changes, like the elimination of classroom exclusions and the reduction of the use of police and courts to address student behavior.